The history behind Alzheimer's disease

While Alzheimer's has always been with us, attempts to understand and identify the disease and its impact didn't come about until very recently in human history.

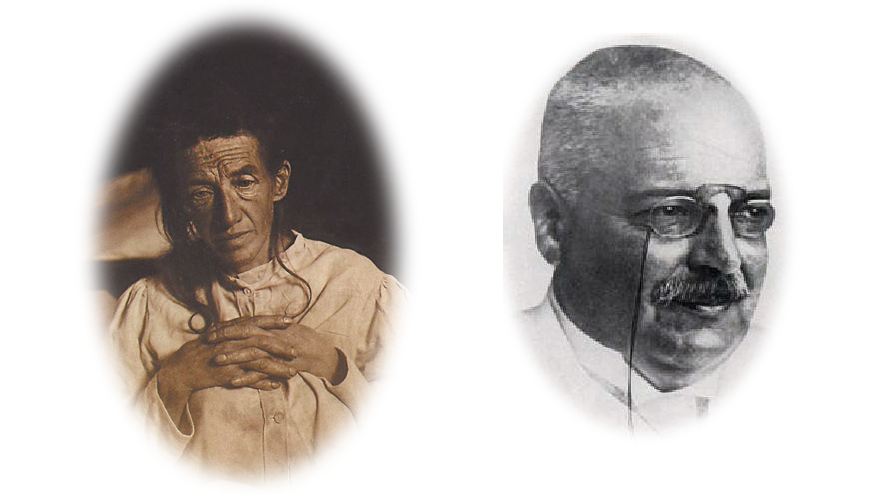

Auguste Deter (left) and Dr. Alois Alzheimer (right)

Late 1890s

In Germany, a woman named Auguste Deter starts finding it difficult to remember recent events. She also sees changes in her behaviour that she can't explain, and is having more problems with speaking and writing.

Auguste, who will turn 50 in 1900, is still quite young for symptoms commonly associated with dementia, a disease presumed to happen only in older adults (aged 65 and over).

1901 and 1902

With her symptoms getting worse and no one to help, Auguste is admitted into an institution. There, a doctor named Dr. Alois Alzheimer learns about Auguste and her unusual symptoms that are happening at such a young age. Interested in finding out more, Dr. Alzheimer interviews her over the next year.

In these interviews, Dr. Alzheimer asks Auguste to recall common facts about her life, and tests her understanding of where she is. Questions like:

"What's your husband's name?"

"How old are you?"

"Where are you right now?"

When Auguste is unable to come up with a response to a question, she commonly answers by saying, "I have lost myself, so to say."

Dr. Alzheimer also observes that, as well as feeling disoriented, Auguste often identifies things by a different name – like calling the pork she was eating "spinach". He also notes that her abilities get worse at night.

1906

After five years in the institution with no treatment for her symptoms, Auguste's cognitive ability has seriously declined. She passes away in April.

Dr. Alzheimer requests Auguste's brain and medical records for studying. Examining her brain, he notes it has shrunk in certain areas, and identifies numerous abnormal deposits. These deposits are the two main changes in the brain that lead to Alzheimer's disease: plaques and tangles.

Dr. Alzheimer concludes that Auguste had a rare form of dementia that affects people aged under 65. He also theorizes that the plaques and tangles he saw in Auguste's brain are related to her disease.

His observations pave the way for more studies on the disease, which is soon named after him.

1910s to early 1970s

Although Alzheimer's disease is getting more attention thanks to Dr. Alzheimer's findings, it's still thought of as a rare form of dementia.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, fewer than 150 scientific articles on Alzheimer's disease are published.

1976

However, this changes after a landmark editorial publishes in a scientific journal, changing the entire world's view on the disease.

In this editorial, American neurologist Robert Katzman describes Alzheimer's disease as a “major killer”, saying that Alzheimer's is:

- The most common cause of dementia,

- The fourth leading cause of death in the United States after heart disease, cancer and stroke and

- A major public health challenge that impacts the entire world.

Katzman's editorial changes the perspective on Alzheimer's from a rare disease to something that affects many more people.

Late 1970s to today

In response to Katzman's editorial, organizations form around the world – the Alzheimer Society of Canada being one of them – to raise funds for Alzheimer's research and increase awareness of people living with Alzheimer's disease and their caregivers.

More than 45,000 articles on Alzheimer's disease have since published, investigating its cause, effects and potential treatments and cures. While no cures for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias have been found, four treatments that can help manage the symptoms have been tested and approved, and more research is being done.

As well, more effort is being done to improve the quality of life of people living with Alzheimer's disease. In Canada, we still have a long way to go to improve our health-care system so it can better accommodate and support people living with Alzheimer's disease, and their caregivers.

However, we know now that putting people living with Alzheimer's disease into facilities with inhumane conditions that offer no viable care or support, as was done with Auguste and many others, decreases their quality of life and reinforces the stigma against dementia.

Instead of institutions, we strongly encourage person-centred care for people living in the late stages of Alzheimer's disease, so they can live comfortably in long-term care that ensures their quality of life.

If Auguste had seen a doctor today, she would be diagnosed with young onset Alzheimer's disease and be connected to resources and help that could support her fight against cognitive decline.

Researchers, advocates and donors around the world continue to fight for a world without Alzheimer's disease.

Last updated: April 16, 2024