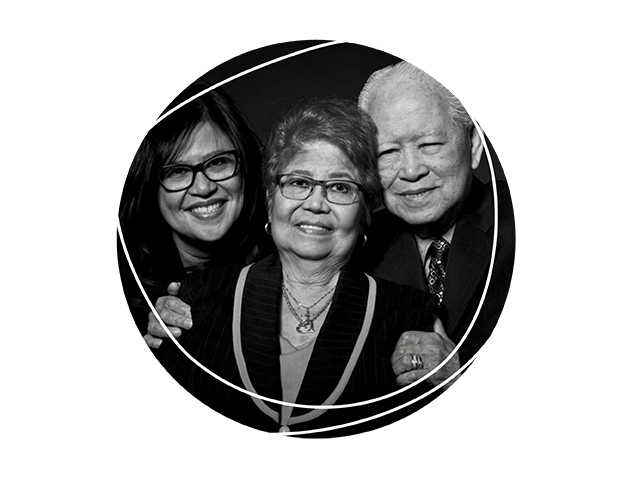

Faces of dementia: Arlene's story

Here, Arlene speaks about being a caregiver during her parents’ experiences with dementia, and she provides perspective on the need for culturally appropriate care and other dementia-care urgencies through a health-care worker lens.

"My father was a lawyer in the Philippines, and my mother was an accountant. Both immigrated to Canada in 1974. My dad sacrificed a lot, because he had to leave his legal profession, which was his passion, to pursue a better future for his children in Canada. An aunt sponsored us, then we lived in a one-bedroom apartment, and a couple of months later we were able to get our own place.

For several years, Dad worked as a mortgage officer, then for the government for a bit, and on the side he pursued paralegal work. He assisted numerous Filipino Canadians to establish businesses, as well as incorporate associations and key organizations like the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and the Filipino-Canadian Nurses Association. He sat on the board of Scarborough Community Legal Services to help newly immigrated Filipino professionals secure employment and pursue accreditation of their degrees in Canada. He believed in unifying the Filipino community and provided a platform for them to be recognized and taken seriously in Canada. At the age of 59, under Bob Rae’s provincial leadership (which sought in part to increase employment equity in the justice system), my dad became the second Filipino Canadian justice of the peace of Ontario.

In 2017—he would have been 83 at the time—we started noticing some changes. He was making some poor decisions when driving. Once, he got lost, and he was driving around Scarborough (where we live) for five hours. He didn’t take his insulin for a month. And he had a stage of delirium.

My mom, at the same time, was starting to have some memory issues as well. Her onset seemed to come after she had shingles, and other complications from her arthritis and newly diagnosed diabetes. She was registered in a falls and balance clinic, and later participated in a memory clinic, as she was starting to forget things. For much of her life with dementia, she has actually had a very crisp memory—remembering birthdates, addresses, and activities when we were young. But her dementia challenges affected her short-term memory, and she would forget when to take medication, how to sequence activities, and what happened at recent events.

During the first few months of COVID, they stayed with me until it was safe for them to return to their condominium. We noticed then, as their memory declined, that they would require full-time care, which became a family affair complemented by caregiving support. Then we found out in December 2021 that my dad’s lung cancer had returned from 20 years prior.

"A short time before he died, he had the wherewithal to know and say in Tagalog, ‘Thank you, I want you to know that I’m really grateful for the care that you’ve provided me and Mom.’ After I recorded that, I was joking with him. He said, ‘Did you record it?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Okay, good. That’s what I want.’"

While his dementia progressed, and he began to speak less and less, we still had special moments when Dad would surprise us with his wit and charm, making jokes and then more seriously asking us about our work and family. For the most part, while little was said, Dad just seemed happy, content, and enjoyed spending time with my mom. A short time before he died, he had the wherewithal to know and say in Tagalog, “Thank you, I want you to know that I’m really grateful for the care that you’ve provided me and Mom.” After I recorded that, I was joking with him. He said, “Did you record it?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Okay, good. That’s what I want.”

Faith is important to my family; we would do the rosary, and Dad would say it with us. But towards the end, he was very weak. I remember us being with a priest; we did last rites the week before he died. My dad was so weak at that time. But he was present. He knew. He wasn’t eating. He was in a lot of pain. We were giving him lots of medication. Soon after, he passed.

Both my sister and I work in health care, and we have been fortunate to have access to physicians for those initial memory assessments for our parents and for other things, like social workers, palliative care information, neurology and more. But the actual process of caring for my parents has been fairly complex.

"I think I’d personally like to see more culturally specific approaches to informing people with dementia about dementia. As my dad’s dementia progressed, he kept defaulting to Tagalog. Having a language barrier may influence diagnosis or in explaining the condition to the person and the family, to help prepare them for what to expect."

My parents have been very fortunate to have three daughters to care for them—from health to finance to property and any administration required to manage my mom’s affairs. I think this is commonplace within the Filipino community, and an unsaid expectation and cultural value—to care for your elderly.

The care of my parents has truly been a family affair. Now, my mom lives part-time with each of us—taking turns living with each daughter. We take turns to be able to provide respite support to each other, and importantly to share some quality time with our mom. To help us, we have caregivers for 10 hours a day while we are working. When I say “family,” I also mean that we have been able to hire caregivers who are family—one is my best friend, another is my cousin, and the third is the nanny who took care of my boys when they were young. In our eyes, they are our family. It has always been important for us, and especially my mom, to be cared for by people who provided a sense of familiarity.

I think I’d personally like to see more culturally specific approaches to informing people with dementia about dementia. As my dad’s dementia progressed, he kept defaulting to Tagalog. Having a language barrier may influence diagnosis or in explaining the condition to the person and the family, to help prepare them for what to expect. We need more physicians pursuing geriatric psychiatry, and we need to support training for those from diverse communities. In the interim, if that is not available, maybe have an advanced practice leader, social worker, or something like that—someone who comes in after the doctor speaks to the family, who has a conversation from a cultural perspective.

For example, in my culture and in my family, I have no problem having my 16-year-old and my 15-year-old take care of my mom and dad. Other cultures might say, “Oh they’re too young, they can’t do that.” Another example: there are a lot of educational materials for dementia that talk about “the caregiver” as a single person, rather than as a network of family and friends. We need more experts and resources that are culturally appropriate.

I’d also say that, in the health-care system, we really need to take a hard look at patient support and dementia—and what that means for home care, where resources are very limited right now. We need more changes, more caregivers trained up and ready. What I think would be nice is if we could have some government subsidies to support home care for people with dementia. In a lot of ways, home care is about dignity—especially from a cultural perspective. Most long-term care homes don’t offer our food or other ethnic foods. If you’re at home, you can eat your cultural foods. You’re still a person. You exist.

We also need to improve dementia care navigation. I’ve had a cousin reach out to me because he knows I work in health care, and he was having issues getting his dad diagnosed. I told him what he needed to do. But what about for people who don’t have someone like me in their family? How are they supposed to know where to go get a memory test?

Also, we still have a shortage of family care practitioners, many physicians are retiring, and that influences dementia care and diagnosis right now. We’re losing continuity of care. People are going to have to figure out how to do it on their own. But no one, really, should be alone with this.”

Photo: Courtesy of Arlene and family.