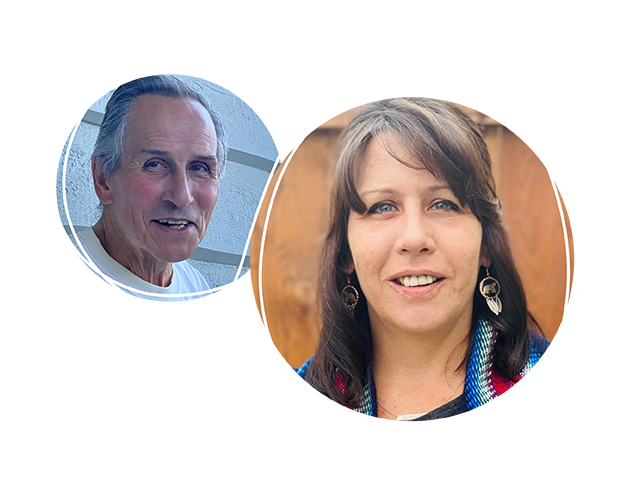

Faces of dementia: Jana's story

Jana Schulz is a social worker and is the past women’s regional representative of Region 4, Métis Nation British Columbia. She is also past president of the Rocky Mountain Métis Association. Here, she talks about her dad, who is Métis and who is living with Alzheimer’s disease.

"My dad is Métis and was born in Edmonton, but he spent the majority of his childhood and youth in Yellowknife. Eventually he went to Hinton, and that’s where he met my mom, who is of European descent. My dad worked there at the pulp mill. And from there they moved to Cranbrook.

Around 2015, might have even been 2014, my dad and my husband were building a fence. And my dad was a drafting engineer. But he could not figure out the right horizontal and vertical measurements. Basically, he was putting the gate on backwards.

After noticing some things such as the fence, I spoke to his doctor and requested a checkup. But the doctor concluded, “It’s normal aging. There’s some decline, but you know, nothing to worry about.” I thought, “No, there’s something else going on.” My mom started documenting things, which we also brought to the doctor, and my dad got a new doctor, then was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2016.

My dad was really never into his culture, but has become more so in recent years, during his Alzheimer’s. I’ll never forget the first time he said to a health-care provider, “I am Métis.” I remember, it just hit me in the heart. Going from not ever talking about it to, more recently, sharing stories. It brings pride.

The cost of caregiving is huge, though. I lost approximately $50,000 in annual income and went below the poverty line by having to switch from a full-time job to a part-time (remote) job. My dad’s disease progressed faster than the health-care system could keep up, and I wanted to better support my mom so that she could support my dad and reduce her risk of burnout. My mom would indicate that she needed respite, so I would go pick him up. I’d take him to nature. In nature, just walking, it would really calm him.

And with the Métis side of things [in dementia care], I started doing research on it myself. Because all I could find was First Nations–based, a First Nations lens brought into it. How can we provide a Métis lens into care? For that, we need the research.

Now Dad’s in long-term care. I know the care aides work so hard there. And in thinking about how to change long-term care, or home care, or community care, there’s still lots that can be done. Like, place a Métis sash somewhere, even if it’s in a picture frame. Think about food. Make it less institutionalized [as a space].

The Métis perspective is about building relationships. In long-term care intake, let’s talk about how I feel I need to be a part of his care plan—because I’m not just a caregiver, I’m kin. And a cousin or auntie or sister or community member should be able to visit too. And Elders. But the westernized [colonial, nuclear] family model used in so many care spaces really blocks any type of traditional healing that way.

"We may not see change in care in my dad’s lifetime. If I can make it so that Métis generations after me can have better care, I’ll have made the ancestors proud."

I’ve been pretty bold in talking about this at Dad’s long-term care home, and it has been a game changer. I went and led two trainings—a lot of staff came, and I talked about an Indigenous perspective, and then put that Métis lens on it. We also talked about intergenerational trauma.

I’ve made clear I want to be part of my dad’s care. If my dad’s awake at 2 o’clock in the morning and disrupting the whole pod, why not call me and say, “Hey, can you come on down?” They laugh because every time I’m there, he falls asleep. I don’t know why it calms, but it works.

Speaking out and advocating has helped. Before, I was burnt out, and I was angry. I was mad at the system; I was ready to quit my job. Now, my voice matters. I knew it did before, but now the right people are listening. At the same time, when I’m asked to share, I always say, “Am I a token? Or do you actually want my input?”

I do wish we had more discussion around dementia stigma in my community—a place I could talk about my fears from a culturally specific lens and use traditional medicines. Again, there are some great resources out there, but they are very First Nations–focused, like using the Medicine Wheel; we in my community don’t necessarily follow the Medicine Wheel.

My mom always called me a rabble rouser. And I am. I think change happens in uncomfortable conversations. But I’m not expecting change overnight. We may not see change in care in my dad’s lifetime. If I can make it so that Métis generations after me can have better care, I’ll have made the ancestors proud.

Even though the dementia journey is challenging, and it’s hurtful and it hurts the heart and the spirit, I believe we’re all put in a path for a reason. My dad is paving the path for Métis after him. And that, to me, fills me with so much love and gratitude because it’s leaving a legacy.”

Photos: Courtesy of Jana Schulz and family.