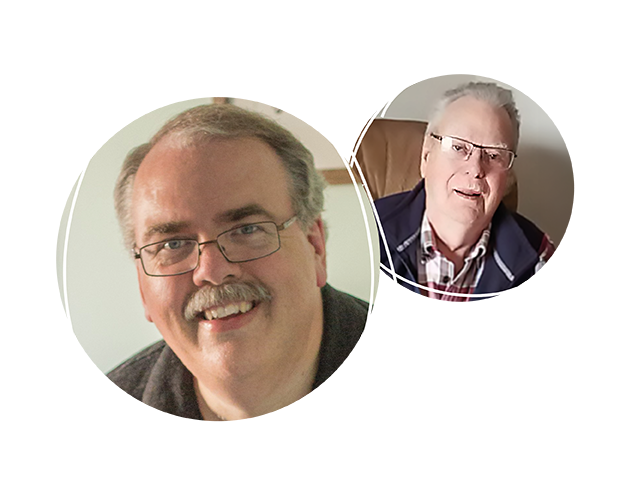

Faces of dementia: Bob and Ron's story

Here, Ron Stewart tells us about the experiences of his father, Bob, who was born Deaf. Bob faced obstacles throughout his life with respect to communication and employment barriers—as well as barriers to dementia treatment and support.

"Dad was born in the 1930s and, as you can imagine, support was limited for Deaf individuals. His parents decided that he should go to the residential part of what was then known as the Ontario School for the Deaf in Belleville, Ontario. The school was located three hours away from his home and he stayed there for several months each year, for 12 years of his life. Each trip back and forth, which he took on the train, also involved struggling to communicate and navigate.

Upon finishing school, his father encouraged him to seek training in a trade. He attended H.B. Beal Secondary School in London, Ontario, to learn auto mechanics. His father was a strong advocate for him and he persuaded the school to allow him to do a practical hands-on testing in order for him to achieve his Class A mechanics’ license. With this, he passed his testing to become one of the first Deaf individuals to obtain this type of licensing in Ontario.

Upon entering the workforce, my dad endeavored to communicate with employers and co-workers who did not know sign language. He would often write on paper or try his best to understand people gesturing with their hands. Small companies didn’t see the need for—or simply didn’t know that—an interpreter would have been helpful for team meetings. It wasn’t until he was hired at the Diesel Division of General Motors, in London, that interpreters were brought in to assist during meetings./p>

In 2015, Dad received a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia. Assessments and diagnosis were difficult for him to understand because he had the academic education equivalent to that of a Grade 2 student. Often there are no words in American Sign Language for such clinical terms. The initial symptoms he experienced included hallucinations of seeing small animals (like mice) or other people in his home. This caused a lot of stress for Mom, who took it upon herself to care for him; she tried to help him understand his diagnosis and what he was experiencing.

Mom was encouraged to enroll him in a day program to give her some respite. He tried attending one, but it didn’t work out as there was no one to communicate with him and no funding for interpreters to help him understand what was happening. The staff tried their best by pointing at him and then at various objects. He found it to be very frustrating. He never wanted to cause trouble (or to get in trouble) so he would often nod and pretend he knew what was happening. Staff would always comment on how friendly he was.

I tried advocating for him by contacting various levels of government and local supports to see if something could be done. We knew that one day he would be in a long-term care facility. We feared that he would be isolated, and that he would have no one to communicate with. I remember him saying to me that his biggest fear was to be locked up in jail or in a psychiatric hospital—he was scared of isolation.

I had a government contact recommend that we should send him to a Deaf longterm care facility in Barrie, three hours away from home. I was furious that it was even suggested to us. How would my family support him if he lived three hours away?

"In 2015, Dad received a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia. Often there are no words in American Sign Language for such clinical terms."

Mom was offered increased hours through PSW support. There are only a few PSWs who can sign and as a result this meant he didn’t receive the required care. Often he was assigned PSWs who couldn’t sign or didn’t have the ability to communicate with him.

Dad had a Geriatric Specialist who was very eager to work with him: she tried her best to understand his situation and to communicate with him. She and her assistant took it upon themselves to learn basic sign language so they could help him feel at ease. They also knew the importance of having an interpreter present for all of his appointments. This was very welcoming for my parents. Mom would often comment how wonderful their appointments were, even if she had to hear that things were deteriorating.

Dad ended up in long-term care in January 2020. He felt isolated and very angry; this was the closest he had come to his biggest fear: being locked up. One nurse tried his best to learn sign language (ASL), but Dad’s dementia was at its worst and he became suspicious of this person’s efforts, which led to more issues. We recognize that the staff did their best, and they were appreciated for their efforts.

Dad passed away in April 2020 from natural causes. And as much as we miss him, I’m thankful he doesn’t have to feel isolated any longer, or deal with the hallucinations from his dementia.

I have tried to estimate how many Deaf people there are in Ontario or in Canada; firm statistics are not available. The rough estimate tends to be that 1% of the population identifies as Deaf. This would approximate to some 153,000 Ontarians and some 396,000 Canadians. In addition to this, sources estimate roughly 3.2 million Canadians are hard of hearing.

The Canadian Association of the Deaf has encouraged federal, provincial and municipal governments to provide supportive living arrangements for Deaf older adults that are Deaf-aware environments designed and intended for their needs—including the company of other Deaf residents. The association also advocates for special training to be provided to workers who support Deaf older adults in various care settings. This could include a requirement to take a basic course in sign language and Deaf culture.

Today in 2023, three years after Dad’s passing, appropriate dementia supports are still very much needed for Deaf individuals and their families. We are still waiting. I share my dad’s story because I hope it can promote change and help others who find themselves in a similar situation.”

Adapted and expanded from an article in Behavioural Supports Ontario Provincial Pulse with the permission of Ron Stewart.

Photos: Courtesy of Ron Stewart and family.