Artist in residence spotlight: Actor, caregiver and thinker - Act 1

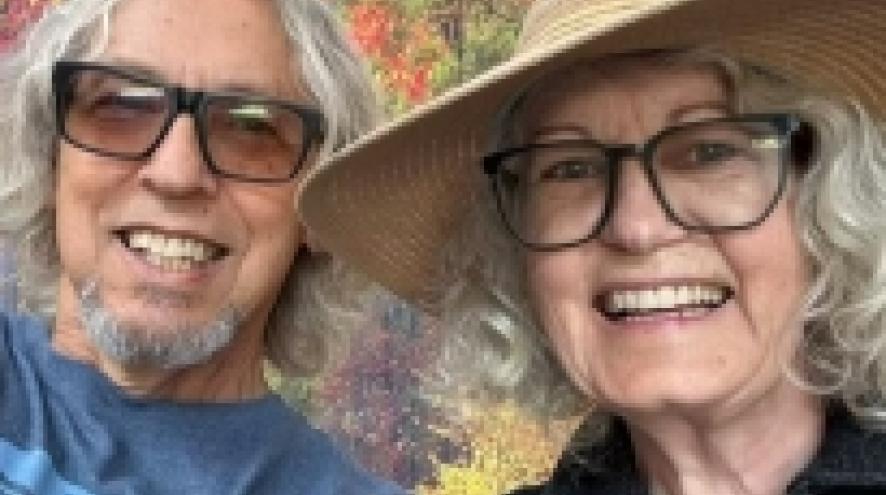

Our Artists in Residence program provides an opportunity for people affected by dementia to share their experience through writing or art. The following reflection was written by Tobias Jesso during moments of respite from caregiving — often while Marsha, his 69-year-old spouse, was sleeping.

As a journaling prompt, I asked myself: Would having a caregiver philosophy help me live a better life?

At the time, I felt desperate, as if I were failing miserably at caregiving. Many days ended in tears of frustration. Was I failing because I’m a man — clocking my time, living my vows, measuring up to an inner standard — trapped on a treadmill of performance? Or was it because Marsha had cared for me for forty-five years, and now that our roles had reversed, I wanted to care for her as she often cared for me? Or, perhaps it was a bit of both?

I knew I needed to find a deeper source of strength — one that could keep me learning, through many trials and errors, how to be present to her. To become a calm, attuned presence, resonating with her communications, building trust as we navigate an uncertain future together. To create a relationship that could endure — generative, loving, and sustainable.

“Please stay

I want you, I need you, oh God,

Don’t take

These beautiful things that I’ve got.”

— Benson Boone

Starting with Philosophy

I began with Albert Camus, whom I first read in my late teens in the 1970s. I’m rereading his work now, revisiting ideas like The Actor, The Rebel, The Absurd and his books all through the lens of caregiving.

This exploration helps me think more clearly about my role. Sisyphus, endlessly rolling his stone uphill only to have it roll back down, has long been an image in my mind when thinking about work and life. Only recently did I realize its roots in those early readings of Camus’ in particular, his work “The Myth of Sisyphus” which ends with the words “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Last year I read Byung-Chul Han’s “The Burnout Society” which offered a different lens for understanding why I was so drained. Both writers give me something rare: philosophical insight that is readable, humane, and short. Dense philosophical tomes have never suited me — not in youth, and certainly not now at seventy, when my mind feels flighty and my comprehension and absorption thinner under stress.

If I misread the philosophers through my caregiving lens, or if I’m comforted by interpretations from ChatGPT that are merely to please me, that’s on me. And if I ever overshare or write something that could seem disrespectful toward Marsha or those with dementia, then I have failed them — and you, the reader, too.

Setting the Scene

My basic desire is simple: to be happy, satisfied, and fulfilled. My core fear is being trapped in pain.

I’ve always tried to relate through humour and storytelling — I’m a Newfoundlander, after all, and stories are in the blood. So too, a thin thread of Indigenous ancestry from my great-great-great grandmother. Connection, story, community, and family are entwined with my caregiving role.

I’m a caregiver to Marsha, who was diagnosed years ago with mild cognitive issues — now progressively worsening.

My current reality often feels like chaos. I feel jolts of anxiety if I turn and she’s not beside me. I’ve lost her a few times, fortunately never for long. I wash, dress, and make her beautiful for each day, doing my best to stay calm and even-tempered. But I am tired — drained of desire — and very emotional, often sliding into self-pity, anger, and sadness.

This emotional drain doesn’t help either of us live our best lives. I know I need routine, structure, and help — from family, from other caregivers, and maybe, from a philosophy of care that can hold me steady on a path so I don’t feel lost and panicked.

To be united with reality and to have a philosophy are related, but not the same. Only mystics and monks seem to fully inhabit their ideals in union with reality. People like me — non-philosophers and imperfect caregivers — can only live ideals in short, flickering moments on life’s stage.

Living as a caregiver is to live inside the absurd — searching for meaning and hearing only silence from the universe. The mind becomes a multiverse of fragments, time loops, and incoherent conversations. Some days, the absurd overwhelms and I forget things too, my thoughts fuzzy — but I digress. Did I mention that I am divergent in my thinking?

Postscript:

I used ChatGPT to help question Camus’ collected works and to summarize specific concepts like The Actor, The Rebel, The Absurd. ChatGPT also helped with context by aligning Camus’ and Han’s philosophies with the caregiver role. I have read the works of both philosophers and I highly recommend them for their readability by non-philosophers. Also, their works are generally very quick reads which is important when you have very little time to yourself.

Actor, caregiver and thinker, Act 2

Actor, caregiver and thinker, Act 3

-----

Tobias Jesso is a retired technology consultant with a master’s degree in computer science and a lengthy career spanning over four decades. He is especially fond of his work for TRIUMF, Canada's Particle Physics Laboratory.

Beyond his professional achievements, he is a devoted husband and father. Tobias and his wife, Marsha, have navigated the challenges of life, including Marsha's cognitive decline. Tobias approaches this journey with love and patience. At age 70, he continues to embrace the lifelong journey of becoming a better person, finding inspiration and wisdom in his spouse's daily teachings. Tobias states, Marsha teaches me as much now as ever and the lessons while hard are infinitely rewarding.

Would you like to tell your story through writing or art? We’ll work with you to find a platform to showcase your work. Email [email protected] to learn more.